BATTLEGROUND:The place of God in the Cinema

I am very interested in cinema, and was busy exploring this interest when I came across a provocative comment by a French, christian academic and film critic. Dr Olivier Clement made the statement that if Christianity was to make any true inroads into the main stream media (and cinema in particular) it needed to "transform the sadness of death into the sadness of God".

What a remarkable statement. Just think; if we were to take any of the famous film tragedies of the last few years and shift the focus of the films away from the sadness of death and onto the sadness of God what dramaticaly rich cinema we could create.

Take "Titanic" for example; if the focus of the tragedy was not the fact that "Jack" died saving "Rose", but on the true story of the young pastor (whose name escapes me) who spent his final moments of life swimming from person to person securing their salvation before he died. What if he had secured Rose and Jack's salvation? How would that have uplifted the nature of the story? Instead of grieving the loss of life we could find hope in the salvation of those souls. Imagine the impact of that on modern cinema.

Popular culture, by the way, has not always been devoid of the Christian message.

If one was to examine any of the popular film genres between the 1930’s and the late 1960’s one would notice a dramatic shift in the positioning of Christ in the spiritual theme of most films. Prior to the 1960’s Christianity was accepted as the foundational belief of the English-speaking film marketplace and it was promoted (if not practiced) by most English, American and Australian film-makers. I have not included other European nations in this discussion because this truth did not necessarily hold for them – the first and second world wars created an anti-God reaction that dramatically coloured the perspective of many of their film makers and cultural movements, many of whom adopted an existentialist, nihilistic, atheistic position: Life is pointless, there is nothing after life, there is no God.

America, Australia and to a lesser extent England were not as directly impacted as northern and eastern Europe by the world wars and so an acceptance of Christian truths continued to be promoted in popular film. Prayer was regularly depicted as a practical option in moments of crisis: i.e Frank Capra’s opening to It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) depicts prayers emanating from a number of houses to ensure the safety of George Bailey, and Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) openly leads his merry men in prayer before embarking on their mission against the evil Prince John.

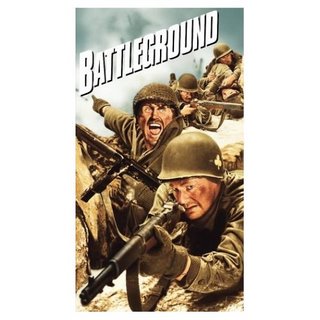

The belief that God had, ultimately, things under his control was evidenced in dramas such as The Grapes of Wrath (1940) where the stoic determination of a family savaged by the depression is reinforced by their faith in Him, and Battleground (1949), when the Chaplain uses prayer to strenghten the resolve of battle weary, drastically outnumbered G.I's before the final battle. This fundamental belief in the justness and, indeed, the existence of God begins to wane by the middle years of the 1960’s.

America’s unpopular involvement in the Vietnam War and their subsequent spectacular defeat at the hands of the Communist Forces of North Vietnam, saw a cultural reaction against “conservative” Christian beliefs and this was evidenced in the spiritual themes of popular culture. The “make love not war” slogan arose, was taken out of it’s spiritual context and used as a tool for dismantling Christian morality and ethics, leading to the other catch-cry of the late 60’s: “If it feels good – do it”.

The ramifications of this cultural shift manifested in all genres of all areas of popular culture, particularly music, theatre and film. Nowhere, however, is the shift away from the sanctity of Christianity more evidenced than in the film genre of the American Western.

God had a tangible hand in the films of John Ford, Anthony Mann, George Stevens and Howard Hawkes, major directors of the Western of the 1940’s and 50’s, with people of God being generally represented as determined, courageous and capable proponents of the Christian Faith. By the mid –1960’s this had dramatically changed.

Suddenly preachers and Godly people were often depicted as weak-willed, morally corrupt cowards, as in Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973), brutal, avenging assassins as played by Robert Mitchum in Five Card Stud (1968), or as insane, deluded sociopaths as realised by Donald Pleasance in Will Penny (1968). Christianity was largely being presented as either a haven for the weak minded, or a toxic pollutant to the mind; something one should avoid at all costs. This positioning has continued for forty years.

The fifties were the golden days of the Biblical epic. From Mervyn LeRoy’s Quo Vadis in 1951 to William Wyler’s Ben Hur in 1959 Christian messaged films saw unprecedented box-office success. But by the mid - late 60’s such efforts were seen as unpopular and unprofitable. King of Kings (1961), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), and The Bible (1966), are considered box office flops. Jesus of Nazareth (1977) was a six hour epic that was made for television, and heavily edited for cinematic release. Although highly regarded by both theologians and film critics it too was not a box office success.

Recent years have seen the release of only a few Biblically based movies. The most notable (and successful) being The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) by Martin Scorsese and 2004’s The Passion of the Christ by Mel Gibson. Paradoxically both were highly successful because they were both highly controversial, both of them flying in the face of accepted theological positions. The Last Temptation of Christ developing the concept that Christ explored a carnal relationship before surrendering to the Cross, while The Passion of the Christ preoccupied itself with the brutality suffered by Christ (events that garner only a passing mention in the scriptures) rather than his death and resurrection – the cornerstone of the Christian faith.

If any positives are to be gleaned out of the success of these two films, it is that they have put Christianity once more on the agenda for potential film-makers. But if we are going to develop that genre and it’s inherent possibilities let’s do it effectively and dramatically, and with theological and scriptural accuracy.

Olivier Clement's suggestion might be the clue that can effect this.

15 He said to them, "Go into all the world and preach the good news to all creation.16 Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned.17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: In my name they will drive out demons; they will speak in new tongues;18 they will pick up snakes with their hands; and when they drink deadly poison, it will not hurt them at all; they will place their hands on sick people, and they will get well."19 After the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, he was taken up into heaven and he sat at the right hand of God.20 Then the disciples went out and preached everywhere, and the Lord worked with them and confirmed his word by the signs that accompanied it.